Art Photographer MAKHism on queer refugee life from Iran to Turkey

- Fictive Mag

- Dec 15, 2020

- 22 min read

Updated: Jan 25, 2021

MAKHism is a queer art photographer from Iran. At 31, he gained official refugee status from the UNHCR in Ankara in 2015, the year he fled from Tehran, where he faced oppression as an openly gay man. Unable to leave Turkey when Trump’s “Muslim Ban” coincided with his asylum claim, he lived in the “satellite city” of Denizli in central Anatolia, where some 5,000 Iranian refugees are permitted to reside in accordance with Turkish immigration.

In 2019, he was without a work permit, waiting for the resolution of his third-country resettlement case, unable to leave Denizli without permission from the local police. In the last weekend of January, he went to Istanbul for the seventh time, with a document allowing only a few days for the duration of the QueerFest, where he participated as the festival’s photographer, also producing a documentary film on the minority refugee experience in Turkey.

He spoke with Fictive at a restaurant in Pera, outside of Kiraathane Literature House (Edebiyat Evi) on a Friday evening, before an event in which an Iranian migrant textile worker spoke about the oppressions they face as an illegally employed queer asylum seeker in Turkey. As the sun fell over the Golden Horn behind us, MAKHism held back tears when speaking about how his mother stood up for him to the end, before he left, and how his three older sisters also helped him transition into exile.

Fashionably dressed, and sporting long dreadlocks, he looked forward to moving to Canada, where he has now called home for just over a month. He has shown his photography in three exhibitions in Turkey, including for a pro-LGBTQI+ exhibition held to coincide with Turkey’s banned Pride March. At the time, he felt he had already spent his best years as a refugee in Turkey, unable to set down roots or form lasting relationships while waiting to hear back from the UNHCR.

I want to learn more about your situation, what is happening here for you.

In September, I finished my fourth year [in Turkey, in 2019]. How many months have passed since then? It’s now four years and a half [that I’m here], since 2015.

At that time, in 2015, you had just come to Turkey?

I came here [to Turkey] in 2015, in September, as a refugee. I didn’t come here to travel and after that become a refugee. I came to Turkey for my first time, and directly, as a refugee.

Which part of Iran are you from?

Tehran, the capital.

Would you share why you left?

I’m homosexual. I’m gay. In our culture, most families don’t accept these feelings, this gender. My father is so religious. I’m the only boy in my family, the last child of my family. I have three sisters. All of them are married. I was the last one. My father believed I should marry. When I finished my university, my father tried to push me to marry. At that time I didn’t have a job. I tried to find a job.

I was a photographer at that time [too]. I started to have a private studio. This is forbidden in Iran too, because I’m a man and the government doesn’t accept me as a photographer to take pictures of women. For that, I should hire women to take a picture. And I’m not into that, because I love to take pictures by myself, not to have another person to take pictures of women.

We made a private studio, and my father didn’t know about these activities. I worked in that studio for two years. After that, my father asked me about my job, and tried to pressure me to marry. Sometimes my father went to the bank to choose a cashier. He said, “Okay, this one is good for you.” He brought me to see women. They are not objects. We should talk together. Because of this I rejected my father.

After this, my father tried to find a girl from family and friends for me. My father told me, “I’ll give you one of my houses. I’ll give you one of my cars. I’ll give you my bank account, and I’ll give you one of my stores to make money. What’s your problem?” I was so shocked. My father is a very rich person. There wasn’t any excuse to decline it, because if I declined, he would ask, “What is your problem? You have money, a house, you should have a woman.”

At this time I hadn’t come out to my mother. Only one of my sister knew about my sexual orientation, because when I was fifteen years old, I went to the psychologist. I was so religious too. I prayed to God. I had this feeling and I didn’t have any knowledge about my feelings at the time. And I went to the psychologist. The psychologist gave me a lot of pills, like Citrolin to make me happy. I started to use them. And after that time, I tried to kill myself, because it was so strange to me. I didn’t see anyone around me who had these feelings. I read some religious books. It is written in Islam and the Quran that I should be killed. I was rejected by my religion.

I was so shocked. I said, “Okay, I’m a Muslim. I pray to God, and the God told me you should be killed.” I was so shocked. I said, “You should leave this religion, or I should kill myself.” This is the reason that I started to use these pills, that maybe I would come back as a normal person. My doctor in those times was such a religious person and told me I should look at women more or see pornography of women to make me more comfortable with women.

I was shocked. I said, “Oh God, I’m not into women, I’m into men, what did you do to me?” Those were such dark years with myself. When I started to use the pills it made me weaker. One night, I was so depressed about my feelings that I ate about 10 pills one time. I fell asleep and when I woke up I was shaking. I thought when I woke up that I was dead, in another world. Then, I woke up and saw myself. All of my body was shaking. The time was about 3AM.

I was fifteen years old. I went to my sister’s room. My sister was awake. She saw me in that position, and covered me. She asked, “What happened?” I told her, “I committed suicide. I think I’m a homosexual. The doctor gave me medicine to make me straight.” My sister laughed at me, and she told me, “Yeah. It’s okay, I’m a lesbian too.” [Laughs]. It was a lie. She’s a psychologist too. She just wanted to support me in that feeling. She said, “It’s okay, I’m a lesbian too. I have a connection with gays too. You are not alone in the world. There’s a lot of people in the world like you.”

From that time, I started to live. Before that time, it was completely dark. And after that, it goes to gray [laughs]. After that I started to have a connection with people. Then, ten years later, my father pushed me to get married. My mother came to me after I was pressured by my father. She came to me and told me that she didn’t know anyone about me. I think, this is my belief, that every mother of homosexual children, they know the difference. There’s a difference. They are not the same. When I was a child, I was playing with girls, painting. I didn’t go outside to play with boys, but made something with my sister. My mother knows. There’s a difference.

When my father started pushing for me to be married, my mother said, “No. He doesn’t want to marry. He wants to be educated more.” Me and my mother were in front of my father, and my father pressured my mother too, to make me agree to marry. One day, my father and my mother fought too much. They fought with body contact, because my mother stood in front of my father and told him, “He doesn’t want to marry.” My father started fighting.

I was traveling for my photography. When I arrived, my sister said, “You shouldn’t go home. You should come to our home, because your mother is here. I saw my mother in such a bad position. She was damaged in the face, and the body. That was one year before I came here, 2014. We left the house with my mother, without anything. After one week, I told my mother my feelings. And my mother was so shocked. I told her, “I destroyed your life because of me. I was feeling so bad, because you protected me but you didn’t know about my sexual orientation.

And after 32 years, they did not divorce, but they separated. She’s 68 years old now. She is living alone. All of my sisters are married. My mother was very depressed at that time in the last year when I was in Iran.

When I left my house and went into the street, I was depressed and had the feeling that maybe my father would find me in the street and try to attack me. I thought of something bad every time I stayed in the house. I started to use the medicine again and the doctor told me I had bipolar. He gave me a lot of pills, bipolar medication. After one year my mother told me, “Iran is not good for you. It is better to leave Iran.” In those weak times, with my mother’s support, I left Iran. I left Iran with my friends helping. I went to Denizli, and four years passed.

How did you get to Denizli?

With my passport, officially. I just bought a ticket. I went to Ankara the first day. I took a ticket to Ankara. When I arrived to Ankara one of my friends had come from Denizli to Ankara because he knows Turkish. He brought me to the UNHCR office. I went there and made an application, and chose Denizli city without any knowledge, because two of my friends were there. It was my first time coming to Turkey.

Now, I’m 31. That was 4 years ago. I passed my golden age as a refugee. My abilities have calmed down. I took pictures all the time, self-portraits. I would upload one collection each month onto my Instagram account. When I came to Turkey, it went to each year, one picture. You know about the depression. “Why should I come here? Why is there no progress to leave? What about earning money?” It’s a refugee sickness, and my abilities calmed down too much.

So, your last year in Iran you lived with your mother?

Yes. It was my golden time.

And how did you begin in photography? Did you study photography in university?

Yes, I graduated with [a degree in] graphic design from a university in the southwest of Tehran. After that I felt that it wasn’t enough for me. My mother gave me a camera as a gift and I started to take pictures and went to the University of Tehran to receive a license in photography. I try to mix these two arts together, graphic design and photography.

Are you staying active at least, despite suffering depression?

In Iran, photography doesn’t earn that much money. Most of the time I earned money from decoration design. Photography in Iran for men is not forbidden, but most of photography is forbidden. You can do wedding photography legally, or fashion design. The only way for photography for us is event photography. I just did some projects for money, most for experience. But when I came here, I started to do more to earn money, but photography is just my hobby. Most of the money I earn is from painting and decoration.

What is your experience with the “satellite city” policy? Did you have to acquire permission to travel from Denizli to Istanbul, for example?

Yes, yes. Actually, we can’t go out of Denizli without the permission of the police.

How does that work exactly?

Actually we can’t get out of Denizli without the permission of the police. The police won’t let us leave Denizli without permission. If some police finds us and asks us, “What are you doing here?” And asks us, “Where is your permission?” If we don’t have it, it’s so risky. Maybe they attack us. Every time I came to Istanbul from Denizli I came with permission from the police. They need the paper, the signature. For example, QueerFest and these companies have a paper to sign and the police accept it.

A normal person can’t give us permission, an invitation. This happen in the past two years, because a lot of Iranian people came to Turkey and Denizli and the police rule changed. There is more security. In the past, when we go to the police to ask permission to visit family they would give it easily. But now, they ask you, “Where do you want to go? How many days? No.” But because a company pays for hotel bills, and a lawyer, they give permission.

What type of documents, for example, do you require going from the UNHCR to Denizli, and now when you leave your satellite city?

There’s an interview the first time you arrive at UNHCR. They ask you, “Why did you leave your country?” You should write a paragraph. And question number two is, “If you go back to your country what will happen to you?” If you answer this question acceptably they start working on your process.

Your case was accepted to begin the refugee resettlement process?

I told them that if I went back to Iran, there wouldn’t be peace. It would be stressful, maybe my father would find me. My father would never accept my sexuality.

How do you feel about the satellite city policy? Is it unjust? How might it be changed?

I think all of the problems come from the world powers, like America. When we arrived in Turkey, there were a lot of refugees from Syria. Okay, people from countries at war should be protected first, to go to the third country. Because of them, we stayed for one year. And after that Trump came, and Trump is anti-LGBTQ, and started banning Persian people. There is not another reason.

After a time, when you are stuck somewhere without any protection from the government, for example, we don’t have permission to work in Turkey. The police made this law. Why? Because we are refugee? Why shouldn’t we earn money? These rules automatically make people go into illegal work, working in hiding. It’s because of the government. Why can’t you hire refugees? For example, there’s a lot of people with a lot of abilities in my city. There’s a sculptor, doctor, dentist, director, musician, chef. They could make some places for refugees in the community.

If they tell people, “Okay, we can hire these people.” Maybe with a little less payment they can make new jobs. Most people in my city, Denzili, have depression because they don’t have a job. What should they do?

How does it feel in the community and as an individual, to be in the city and to have to go to the police when you want to leave?

It’s like a jail, but in a jail you enter with a crime. But we came to the city without any crime, and the jail is the size of a city. It’s not a room, or a yard. After four years, it becomes small, like a jail. There are not interesting places in the city and you shouldn’t leave without permission.

How is life in Denizli? Are there certain pockets where people go, centers, locations where people hang out? What’s going on there in terms of the Iranian community? Having been there for years, you must have seen how life goes, how people try to enjoy.

Denizli is a little bit of a religious city, close-minded. You see a lot of women in hijab there. With my appearance, people look at me so much. This is the reason I hide myself in the house, and don’t go in the street, because of my appearance. They might look at you and attack you if they’re anti-homosexuality and anti-trans.

The people in Denizli try to make community for themselves without any rules. There are a lot of Iranians in Denizli who make parties, events, guided tours to other cities. But there aren’t any rules inside that. All of the people have a dark, depressive side. There aren’t jobs. Some people are trying to make food at home and sell it without permission, make clothes. There is underground living in Denizli so much. You can’t trust people so easily.

Many people try to have a group of close friends, like a family. After two years I haven’t tried to have a connection with people because it’s too dark. They stick there without any news from UNHCR. Most of them are depressed.

Have you tried to switch cities?

No, because, the police of Denizli are so sensitive about this. I wanted to change my city to Yalova, near Istanbul. It’s smaller than Denizli. If I go to Yalova I should be living in Istanbul, but it’s hard to go there, because for Istanbul I should have medical problems, or to find a job with someone who hasn’t found anyone else with my abilities, and they write the paper that I give to the police, saying, “I searched a lot and we didn’t find anyone else with these abilities. We need to hire this person. Maybe, 50/50 the police lets me move from Denizli to Istanbul. But in my situation right now, it’s so risky, because this movement needs a lot of movement.

In Denizli maybe we earn money daily, because there aren’t fixed jobs. We think, “Okay, I should earn money for this week only.” Not more than one month. You should be so lucky to find a job with a monthly payment, something like that. After four years, as I’m waiting for my visa and all of my process to finish, now to change my city like this is so risky. If I come back to the time of two years ago, or three years ago, yes maybe I could do that, because in Istanbul there’s a lot of work for me, painting on the wall, photography. But in Denizli there are no such jobs. There is only one gallery for government exhibitions. They don’t have knowledge about art.

Do refugees in Yalova need permission to come to Istanbul?

They can [leave without permission], but in this last year, after the bombing attack in Istanbul two years ago, the police were more sensitive about refugee people. They started making more security. One of my friends was living in Yalova with a house in Istanbul and he told me that when he tried to take a boat back home there was some police checking the way. They asked, “Who are you?” And they took his ID card. Now is so risky. Because here there is a lot of pressure. This is enough for us. We’re thinking, “What happened to my life?”

Have you seen the QueerFest in Denizli over the years?

Last year, they came to Denizli.

You saw it there first?

Yes. This is my first time in QueerFest in Istanbul. A month ago I was in the “Istanbul art show” at Hilton Hotel. I joined the exhibition as a photographer. It was such a good experience for me. One year before that I was in the “Sınırsız” [Boundary / Less] exhibition at Kiraathane, for gay pride.

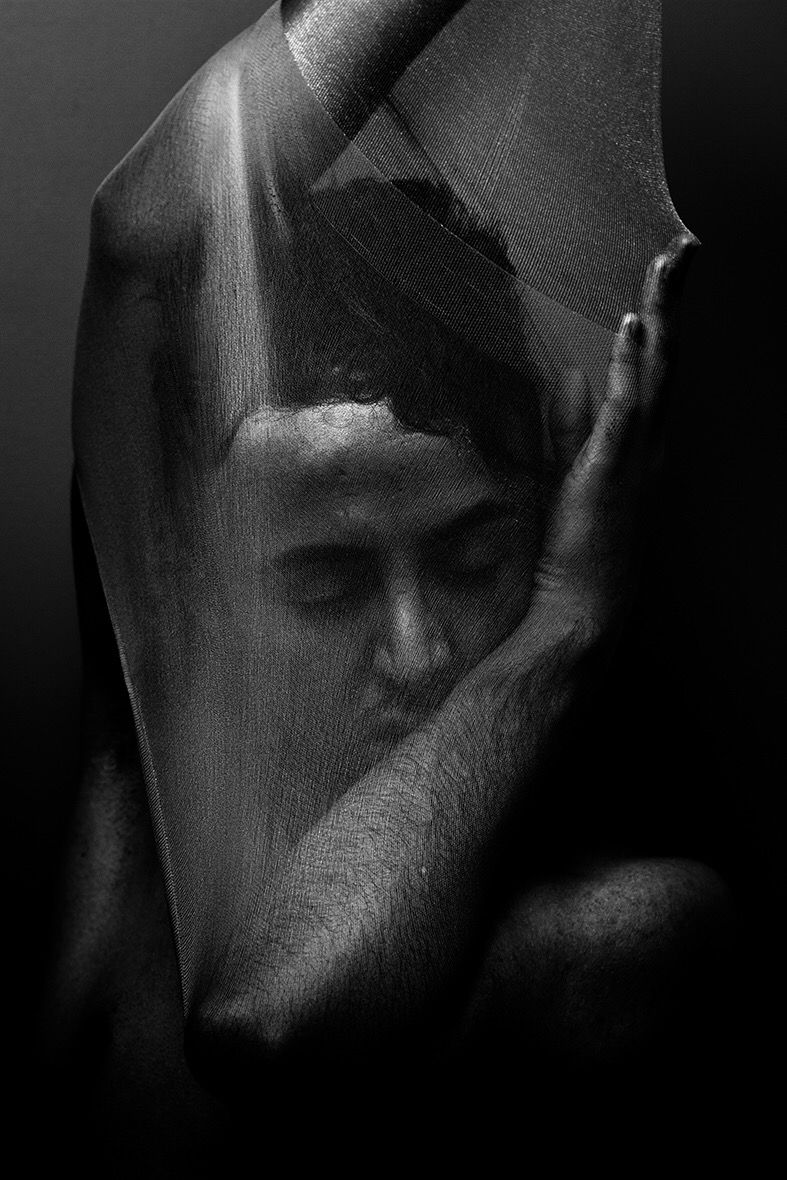

I showed the forbidden pictures from Iran, when I took a lot of queer art of myself, as a self-portrait and it was forbidden in Iran. I was stressed to upload it in my accounts. I showed these in three exhibitions [in Turkey]. The first one was in Denizli. You can see them on my Instagram [@makhism].

When was the first time you came to Istanbul from Denizli?

I came the second year I was in Turkey, to visit my family. After that I haven’t visited them, because my mother’s passport is expired, and my father hasn't signed to let her see me. I did not see her for two years.

Now, you’re waiting for the UNHCR to resolve your case?

Now, I’m just waiting for my medical insurance, because it’s expired. After eight months it expires. When I last took out medical insurance two years ago, they told me that I would be in the US between two weeks and two months. And they didn’t give me a ticket. My depression started in those times, two years ago when Trump came.

Do you know, you pack all of your stuff. I was waiting, waiting for my flight. You can’t make plans for your future in Turkey. You can’t buy anything. For two years I feel like this if I want to go somewhere, or start working somewhere. For example, I lost a great job because of my situation. I told them, “I’m waiting for my flight.” They told me, “What is your situation in Turkey?” I tried to tell them the truth. I said, “I’m waiting for my flight for two years. I don’t know when.” They said, “Okay, if we hire you, it’s too risky for us, maybe next week you should go. What would we do?”

All of my roots have dried. For two years, I’m just trying to live in the moment without any plans for the future. I try to talk to myself, saying, “Okay, just catch the moment. Don’t make a plan for yourself, because there isn’t...”

So, at anytime you could be contacted to receive your ticket?

Yes, maybe this week. I don’t know exactly. I called UNHCR to ask, “Please give me a time? Give me a time to plan my life. I should know, I’m human. I should know about my future. Okay, if you don’t want me to go to America, for how many years should I stay waiting, waiting?”

I lost one of my relationships because of this situation. I was falling in love deeply and so happy about this feeling. And when we started to make a plan to live, he told me, “You don’t know about your future. Maybe next week you will go. I can’t have a relationship with you. It’s better to cut it with you.” What he said was true. I left my family. I’m such a relationship person. I can’t meet guys one by one to have a connection. I prefer to have one person in my life. I said, “Okay, you should change your life because of this situation.”

Is there a film, or event, at the festival this year that you’re looking forward to?

I’m making a documentary. It’s good for me. Two Iranian refugees, [including] a transsexual person, are introducing the festival. I tried to make a movie with them, coming out of Denizli, and returning exactly to the permitted time. And the name of the documentary is “Izin”. It’s the name of the permission [policy] in Turkey. In Turkish, it’s “Izin” [which literally means permit in English]. You should come out and come back again to the jail.

I borrowed this [camera] because I don’t have a camera to make a movie. This is a go pro and there isn’t any LCD. I just take a movie and it’s maybe shaking. [Laughs]. I should edit it well.

Are you following specific individuals as part of the documentary narrative?

Yes, my four friends, when we come out and we go back. Not at the police office, because it’s forbidden to make a movie [there]. When I received this [camera], it was two hours before our flight to Istanbul. The manager of the festival sent it to me. I chose three of my friends for the festival and asked them to permit us, that we’re coming with them to make a documentary, and take some pictures for your events. They accepted. I hope it becomes a queer movie for the next QueerFest, about the [satellite city] situation.

Do you know, when you are in jail, the owner of the jail gives you food, a place to sleep, and you don’t need money. But [in a satellite city] you are in jail and you should work without permission, and if you don’t work you don’t have money. You can’t leave the jail. This is such a bad situation.

When you request to leave the city, how long does it take for them to respond and process your permission?

When they see your schedule, for example this festival wants us for five days. So they add one day for going, one day for returning on the permission. It’s for seven days. At the airport they see our “izin” [permit]. “Okay, where is your izin? Okay, you can go.” Our ID card for Turkey doesn't work in this moment. They are writing on the back of our ID card that it is only valid in Denizli. It’s not for other cities. You should attach the [permission] paper.

It takes a day just for this [izin, permission slip]. We go to the police office at 5AM, and stand in line. At 8AM the office is open. We receive a number. We return at 10AM. They receive our documents and papers. They tell us, “Go and wait for your ‘izin’.” This time, we received it before 12PM. We were shocked at how quick it was. Before, we waited till 6PM. For a whole day [at a time] we waited for a piece of paper. There are a lot of Syrian and Afghan families.

After four years, I was telling one of my friends, I’m waiting for the day when I can get rid of this refugee thinking. What is life without this feeling? Is it peaceful or not? Is it kind or not? I am just waiting for this feeling. What will happen to me? For example, the day after tomorrow we should come back to Denizli. Everything comes back again, the dark side of the people, the depression. When we came to Istanbul it’s like bringing children to kindergarten or Luna Park [laughs].

How many times have you left Denizli?

I left Denizli three times for exhibitions; two times for ICMC [International Catholic Migration Commission], interviewing for the embassy of America, one time for medical [issues], one time for visiting my family. Only seven times have I come to Istanbul in four years. And every time I have to get permission.

How many Iranians do you think are in Denizli?

Maybe 5,000, or more.

How many came to the festival from Denizli?

Just five of us. Shaya, Fahriman, Mouna, Artin and I.

I was talking to a young woman from Kabul and she told me of how people from Iran come overland to Turkey.

Yes, most of the Persian people, Iranian people, come without passports, walking, without permission, by the mountains. Two of my friends came out of Iran like this.

How do you feel to be in a similar situation with Syrian people, and with Afghan people? Afghan people speak a language similar to Persian, yes?

Yes, we can understand [Afghans], but they speak like the older Persian. Actually, they speak right Persian. They speak a Parsi and Urdu mixture. After a time, the Farsi language became modern, and received a lot of words from French and English, but when Afghan people speak in front of us we can recognize what they say. There are a lot of the same words.

Do you have feelings about the fact that Syrians are able to move around within Turkey, but everyone else seeking asylum in the country is not?

There is a bad feeling. Syrian families receive money from the Turkish government, for each person. It is maybe more than 700 liras each month. The government of Turkey gives them money. But they don’t give any money, not one lira to the Iranian people. And most Turkish people think that we receive the money too. They look at us like this. I answered for Turkish people several times. They ask, “You came here and receive the money from our government. You receive our money. Why did you come here?” I said, “Sorry, we didn’t receive even one lira.”

The only thing the government gives us is a 30% discount for medical insurance, but we should pay for it. There isn’t anything else. We don’t have permission to work. We don’t have permission to go out of our city. Iranian people have parties every weekend. You can see a lot of party events in Denizli made by Iranian people. But you can’t see one party for Afghan people, or Syrian people. There’s a lot of Persian nights in our city. The Turkish people look at us like this, that we have fun, we don’t have problems.

But don’t you know this is the style of Persians. They earn money to spend it for fun to make themselves happy. When you see the Persian, Afghan and Syrian, you can recognize which one is Persian, but it’s only by appearance because maybe that Persian person doesn’t have a home, no ceiling over their head or food. But they try to keep their appearance well. This is a problem, how the Turkish people judge us. The Persian people in my city rent a car and go on vacation. They are refugees, they go without permission. They think the luxury living is so important. Every week, they have pictures [laughs]. I’m not into this style but I see it a lot.

Do you see African refugees as well in Denizli?

Not so much. There are some African university students in Denizli, but most of them are in Istanbul.

When the festival goes to Denizli, does it change the community atmosphere? Do many people go?

Only LGBTI+ people come, maybe from Turkey, and of Denizli. It’s so small. It’s three days. They rent a cinema salon, or event salon.

As you say, there are some 5,000 Iranian refugees in Denizli, and there are many issues besides LGBTI+ that have caused them to leave Iran.

Yes, there are religious refugees, political refugees. We have a lot of LGBTI+ in Turkey, but they hide themselves. They didn’t come out to the community. You can’t see all of them at these events. They hide themselves. You don’t know who is a refugee. I have a lot of LGBTI+ friends in Denizli, but we don’t know most of them because of the security issues. They hide.

My understanding of LGBTI+ issues in Iran is that the government can execute homosexual people by law. How much was that a part of your case for asylum? You left because of family issues not because of government issues? Is there a connection?

The government doesn’t accept us. There is a rule in Iran, in Islam, if you two or three adult persons see you in the act of [gay] sex they can go to a lawyer and say they had sex together and after that, when the lawyer accepts it, they can kill you. They can punish you with a whip. This is forbidden, completely forbidden.

We don’t have any rights as LGBTI+ in Iran, they can do anything to us, maybe we go to jail, because they don’t accept us. I didn't promote my artworks as queer art. When I started taking pictures as queer art, I didn’t know anything about queer art, but I did it. After a time, I saw that there are a lot of people doing it this way. I was shocked and afraid of the government. If the government told me, “Why you take this?” What should I do?

The basic thing is we are afraid of the government. When you have a problem with your family you can’t have a good relationship with the government. I can't rent a house by myself in Iran, because no one would rent me a house, because I’m a single boy. Maybe if I have a lot of money to just give to the owner, extra money, two times more, maybe like this. But if you want to have a single home, they ask, “What do you do in your home?” This is our culture.

Are you planning more exhibitions with your photos?

Here, I don’t have [plans]. I just promote all of my artworks from Iran. I just give them to exhibitions to show them. I don’t give new ones, because I don’t have resources here. And it’s not reasonable for me to buy them just for shooting. This is the reason I don’t have any new collections. But I’m trying to paint. Maybe I’ll join as a painter in the next [exhibition]. But you know to create art needs a clear mind. Now, if I’m painting, all of my painting goes into a deep depression, dark side, and maybe no one wants to buy my painting, because it’s so dark. First of all, I really need a clear mind. And after that, create something.

I’m trying to understand the practicalities and details of what refugees here go through, and how they feel about how certain policies might change? I can imagine how you wouldn’t put energy into how to change things when you’re trying to survive.

There’s no way. You’re in a house of cement. Every door is closed. There aren’t any keys. You’re just waiting, wishing, and patient. There is not anything else. UNHCR just sends me a message to say you should wait, for two years. I called them to ask, “Please, tell me another sentence, another word. Instead of please wait.” I sent an email, saying I’m in a bad position, I’m depressed. They called me to say, “You should just wait.” Our minds are so weak when we start talking with the UNHCR, it takes our whole day.

If I stay in Turkey forever, what should I do? Sometimes I think, maybe I should be a resident of Turkey, but I don’t like Turkey. The best cities in Turkey are Izmir and Istanbul, by appearances, but inside it’s not good. Istanbul is like a sin city for me. I want to live in a place for living, that’s peaceful. I talk to myself, and say, “Be patient.”

People go to Greece and the EU to try to get out of Turkey. Have you thought of it?

Without permission, they just take a backpack, with someone to take them by a forbidden way, they go to Greece, and after that Italy, Europe and Germany. But I’m not this kind of risky person, because four years ago one of my friends, who is now a resident of the UK, told me you can go to the UK as a student and after that, when you pass one year, you tell the government you want to be a refugee because my family knows about my sexual orientation. I told him, “Okay, I don’t have enough money to apply for university in the UK.”

I want to tell you about another experience with the government of Denizli. There is an ancient place in my city, Pammukale, Hierapolis. A government restoration [project] tried to find people to recover the sculptures from the ground. They couldn’t find Turkish people. They had a connection with my close friend, because he graduated from restoration in Iran. They took me for this project for two weeks. At this time, I was looking for a job. They paid about 700 TL, but if they hire Turkish people they should pay 10,000 TL. This is the reason we are refugees. And the last day they didn’t let me go inside the place, because of my appearance.

Comments